High fasting insulin—measured after several hours without food—may coincide with autoimmune activity that affects insulin production or signaling, what people commonly notice, how clinicians typically evaluate it, and the general strategies used to manage day-to-day health. You’ll learn the difference between insulin resistance influenced by immune processes and other causes; what signs often prompt testing (fatigue, shifting weights, variable glucose numbers, and a family history of immune conditions); and how routine laboratory evaluations—including fasting insulin, fasting glucose, HbA1c, and relevant autoantibody tests—fit into a clinician’s assessment.

Management discussion stays educational and non-prescriptive, focusing on balanced nutrition, consistent physical activity, clinician-directed medical care (including immunomodulatory options when appropriate), ongoing monitoring, and stress control. This content is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for personalized advice from a qualified healthcare professional.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only and does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. It does not replace a qualified healthcare professional’s judgment, and it should not be used to make decisions about your personal care. Always consult your licensed clinician—especially if you have symptoms, abnormal lab results, or questions about medications or tests. Never ignore or delay seeking professional advice because of what you read here; if you think you may be experiencing a medical emergency, call your local emergency number immediately.

What Is Fasting Insulin?

Fasting insulin is the amount of insulin in your blood after an overnight fast (commonly 8–12 hours without food), and it’s typically reported in µIU/mL (mIU/L); clinicians use it alongside fasting glucose and HbA1c to understand how your body handles sugar. Because insulin helps move glucose into cells, a higher-than-expected fasting insulin can signal that cells are less responsive to insulin (insulin resistance)—the pancreas compensates by releasing more insulin to keep glucose steady. While lifestyle factors often drive this pattern, some people have immune-related processes that affect insulin production or signaling, which can complicate interpretation. A single fasting insulin result does not diagnose a condition on its own; it’s one data point that must be read in context—medical history, symptoms, medications, and additional labs—by a qualified clinician.

What Is Fasting Insulin?

Fasting insulin is the amount of insulin in your blood after an overnight fast (commonly 8–12 hours without food), and it’s typically reported in µIU/mL (mIU/L); clinicians use it alongside fasting glucose and HbA1c to understand how your body handles sugar. Because insulin helps move glucose into cells, a higher-than-expected fasting insulin can signal that cells are less responsive to insulin (insulin resistance)—the pancreas compensates by releasing more insulin to keep glucose steady. While lifestyle factors often drive this pattern, some people have immune-related processes that affect insulin production or signaling, which can complicate interpretation. A single fasting insulin result does not diagnose a condition on its own; it’s one data point that must be read in context—medical history, symptoms, medications, and additional labs—by a qualified clinician.

Possible Causes

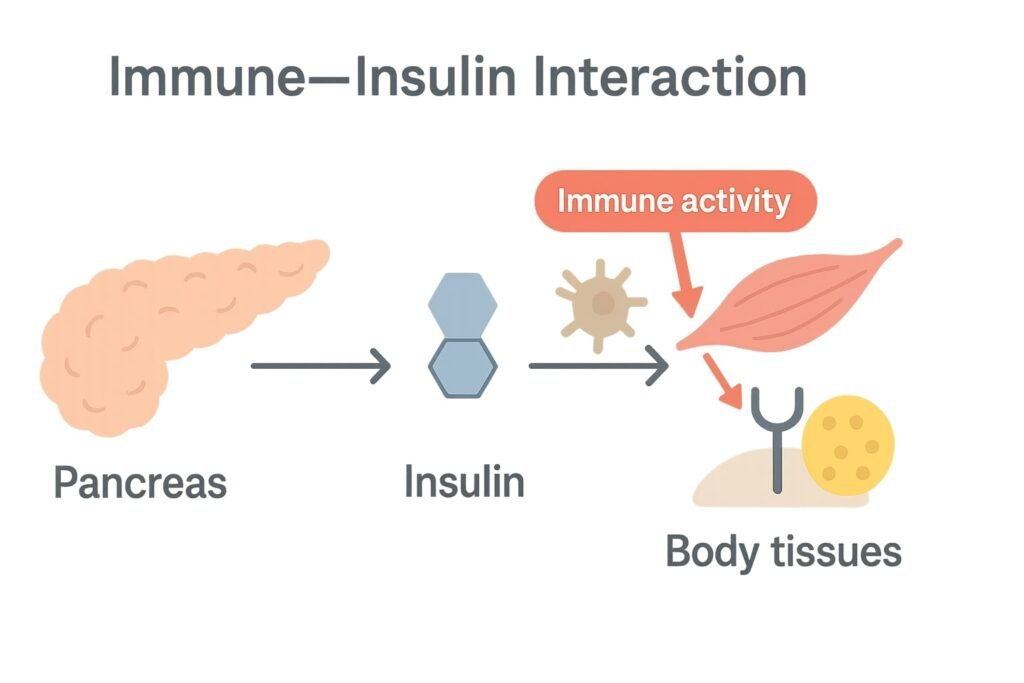

High fasting insulin can arise from more than one pathway: classic insulin resistance (cells respond poorly, pancreas compensates), autoimmune activity that interferes with beta-cell function or insulin signaling, and broader inflammatory states that distort glucose control—often interacting with overnight hormonal patterns that nudge morning readings higher. Because these factors can overlap, clinicians usually read fasting insulin alongside history, symptoms, and complementary labs rather than as a single deciding metric.

Insulin Resistance with Autoimmune Influence

When baseline insulin resistance is present, even low-grade immune activation can amplify it—cytokine activity may blunt insulin signaling in muscle and liver, pushing the pancreas to release more fasting insulin to maintain stable glucose. Some people notice the effect most in the morning, when counter-regulatory hormones (e.g., cortisol) naturally rise; immune-related stressors can intensify this pattern, making an elevated fasting result more likely on certain days.

Related Autoimmune Conditions

Immune responses directed toward pancreatic beta cells or insulin-regulating proteins can alter output and stability over time. While classic immune-driven diabetes often involves lower insulin production, earlier phases or mixed presentations can show compensatory increases in fasting insulin as the body attempts to keep glucose within a normal range. A personal or family history of autoimmune disorders raises clinical suspicion and may prompt islet-autoantibody testing as part of a broader work-up.

Inflammatory Responses

Persistent inflammation—whether tied to autoimmune conditions or other sources—can disrupt insulin signaling pathways and increase hepatic glucose output, leading the pancreas to secrete additional insulin to overcome impaired uptake. This state can fluctuate with illness, sleep quality, medications, and daily stress, which is why readings (fasting insulin and glucose) may vary from test to test even without major lifestyle changes.

Key Indicators (What People Commonly Notice)

People who suspect an autoimmune influence on high fasting insulin often report frequent fatigue, weight changes (gain or difficulty maintaining), variable glucose readings (fasting or post-meal), and a personal or family history of autoimmune disorders; because day-to-day factors like sleep, stress, intercurrent illness, and medications can sway results, clinicians typically look at patterns over time rather than a single number and interpret these signs together with history, exam, and labs to decide what testing or follow-up is appropriate for you.

Diagnostic Methods

Clinicians typically combine history, examination, and targeted testing to understand whether elevated fasting insulin reflects routine insulin resistance, an immune-related process, or both; the goal is to look for patterns over time and align findings with the person’s symptoms, medications, and overall metabolic context rather than relying on any single result.

Common Labs & What They Assess (Educational Table)

| Test (educational) | What it assesses | Typical clinical context | Units / notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting insulin | Baseline insulin output after an overnight fast | Read alongside fasting glucose/HbA1c to understand insulin resistance vs. other patterns | µIU/mL (mIU/L) or pmol/L (lab method varies) |

| Fasting glucose | Morning blood sugar after an overnight fast | Interpreted with insulin and HbA1c for overall glycemic picture | mg/dL (U.S.) or mmol/L |

| HbA1c | Average glycemia over ~3 months | Helps contextualize fasting and post-meal patterns | % (method-specific considerations apply) |

| C-peptide | Endogenous insulin production | Useful when distinguishing own insulin secretion from exogenous insulin; context for beta-cell function | ng/mL or nmol/L |

| Islet autoantibodies (e.g., GAD65, IA-2, ZnT8, IAA as appropriate) | Immune activity directed at beta-cell–related targets | Considered when autoimmune contribution is suspected | Qualitative/quantitative; lab-specific references |

| OGTT with timed insulin (if ordered) | Response of glucose and insulin after a glucose load | Maps secretion vs. sensitivity dynamics | Timed values (lab protocol–dependent) |

| CRP or other inflammatory markers (if indicated) | Systemic inflammation context | Adds background when inflammation is suspected | mg/L (assay-dependent) |

Educational context only; interpretation belongs with a licensed clinician familiar with your history and local lab standards.

Laboratory Tests

Core labs often include fasting insulin, fasting glucose, and HbA1c, with optional oral glucose tolerance testing (OGTT) with timed insulin draws to see how secretion and sensitivity change after a glucose load; a C-peptide level can help gauge the body’s own insulin production, while islet-autoantibody panels (e.g., GAD65, IA-2, ZnT8, IAA as appropriate) assess for immune involvement, and inflammatory markers (such as CRP) provide context when systemic inflammation is suspected; thyroid and other autoimmune screens may be added based on history.

Medical & Family History

A detailed timeline of fatigue, weight shifts, glucose variability, sleep and stress patterns, and any steroid or other medication exposure is paired with questions about autoimmune conditions in the patient or family (for example thyroid disease or celiac disease), prior infections or illnesses, and nutrition and activity routines, so that lab findings can be interpreted against real-world factors that influence insulin dynamics.

Physical Examination

Beyond general assessment, clinicians may track waist circumference and blood pressure, examine skin, hair, and nails for endocrine or immune clues, and perform focused thyroid and neurologic checks; these observations help differentiate predominantly metabolic patterns from those where immune activity may be contributing.

Further Assessments & Referrals

When indicated, clinicians may recommend short-term glucose logging or continuous glucose monitoring to capture day-to-day variability, consider selective imaging only for specific concerns, and coordinate care with endocrinology and, when appropriate, rheumatology, aligning testing and follow-up with the person’s symptoms, risk factors, and preferences.

Management Approaches

A clinician-guided plan aims to support insulin sensitivity, reduce glycemic variability, and account for any immune involvement without making diagnostic claims; the focus is practical day-to-day steps that complement your history, medications, and lab pattern over time.

Nutritional Adjustments

A balanced, fiber-forward pattern (vegetables, intact whole grains, pulses, lean proteins, healthy fats) helps smooth post-meal swings so fasting readings are less volatile; many clinicians also emphasize consistent meal timing—especially the evening meal—to reduce overnight variability, and recommend working with a registered dietitian to tailor portions, carbohydrate distribution, and satiety strategies to your lab trends and symptoms.

Physical Activity

Regular movement improves insulin action in muscle and liver; a commonly referenced baseline is ~150 minutes/week of moderate aerobic activity plus 2–3 resistance sessions/week, scaled to your energy, sleep, and any autoimmune symptoms so training supports—not aggravates—overall recovery; non-exercise activity (walking throughout the day, light mobility) meaningfully adds to the effect.

Medical Treatments

When clinically indicated, clinicians may use insulin-sensitizing agents or other glucose-lowering therapies and adjust doses based on your response, side-effects, and comorbidities; selective use of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) or structured glucose logs can reveal fasting vs post-meal patterns that inform targeted medication, nutrition, and activity changes under supervision.

Immunomodulatory Treatments

If testing points to immune involvement (for example, positive islet-related autoantibodies), specialists in endocrinology—and when appropriate, rheumatology—discuss immunomodulatory options within established safety parameters; any consideration of beta-cell preservation or immune-modifying strategies is individualized and managed by the treating specialist.

Regular Testing & Monitoring

Follow-up typically tracks fasting insulin, fasting glucose, HbA1c, and, as appropriate, C-peptide or repeat autoantibodies at clinically reasonable intervals—often every 3–6 months—with cadence adjusted to symptoms, therapy changes, and new findings; CGM metrics (including time-in-range) or structured logs help translate day-to-day variability into practical adjustments.

Stress Control

Because the stress response can elevate counter-regulatory hormones and tilt morning numbers, simple, repeatable practices—steady sleep windows, brief breathing or mindfulness blocks, light stretching, and realistic workload boundaries—can lower background strain and support steadier insulin and glucose patterns alongside your broader care plan.

Units & Conversions for Global Readers

Fasting insulin (insulin units)

Labs commonly report fasting insulin in µIU/mL (mIU/L), while others use pmol/L. A practical approximation many clinicians reference is 1 µIU/mL ≈ 6 pmol/L. To switch units, multiply µIU/mL × 6 = pmol/L, or divide pmol/L ÷ 6 = µIU/mL. Because conversion can vary with assay methodology, always read results against your lab’s own reference interval rather than applying universal cutoffs.

Blood glucose (sugar units)

U.S. reports typically use mg/dL, whereas many countries use mmol/L. A quick mental link is 1 mmol/L ≈ 18 mg/dL. Conversions are straightforward: mmol/L × 18 = mg/dL and mg/dL ÷ 18 = mmol/L. These numbers help international readers interpret values without changing the clinical context.

C-peptide (when ordered)

If your clinician includes C-peptide to gauge endogenous insulin production, you may see ng/mL or nmol/L. A commonly used conversion is 1 ng/mL ≈ 0.331 nmol/L. Convert by ng/mL × 0.331 = nmol/L or nmol/L ÷ 0.331 = ng/mL. Use these only for orientation; interpretation belongs with your clinician and the specific lab method.

Note: Conversions are educational aids—not diagnostic thresholds. Discuss any personal targets or ranges with a qualified healthcare professional familiar with your history, medications, and testing standards.

Units & Conversions for Global Readers

| Measurement | Primary unit | Alternate unit | Quick conversion (approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting insulin | µIU/mL (mIU/L) | pmol/L | 1 µIU/mL ≈ 6 pmol/L |

| Blood glucose | mg/dL | mmol/L | mmol/L × 18 = mg/dL; mg/dL ÷ 18 = mmol/L |

| C-peptide | ng/mL | nmol/L | 1 ng/mL ≈ 0.331 nmol/L |

FAQs — Quick Answers

High fasting insulin reflects how hard your pancreas is working to keep glucose stable (often due to insulin resistance), while high fasting glucose shows that blood sugar itself is elevated; you can have elevated insulin with normal glucose early on, which is why clinicians read both together with HbA1c and sometimes OGTT to understand sensitivity vs. secretion.

Not always. It can signal insulin resistance before glucose rises or occur transiently with stress, illness, poor sleep, or medications; clinicians look for broader patterns—waist circumference, blood pressure, lipids, HbA1c, fasting glucose—before labeling prediabetes or metabolic syndrome.

HOMA-IR is a calculated estimate of insulin resistance using fasting insulin and fasting glucose; it’s a research-informed tool some clinicians use for context, but decisions typically rely on the whole picture—history, symptoms, glycemic variability, and confirmatory labs—rather than a single calculated index.

C-peptide tracks your body’s endogenous insulin production; pairing C-peptide with insulin/glucose helps distinguish high insulin from injections vs. your own secretion, and offers clues about beta-cell function when autoimmune activity or long-standing insulin resistance is being considered.

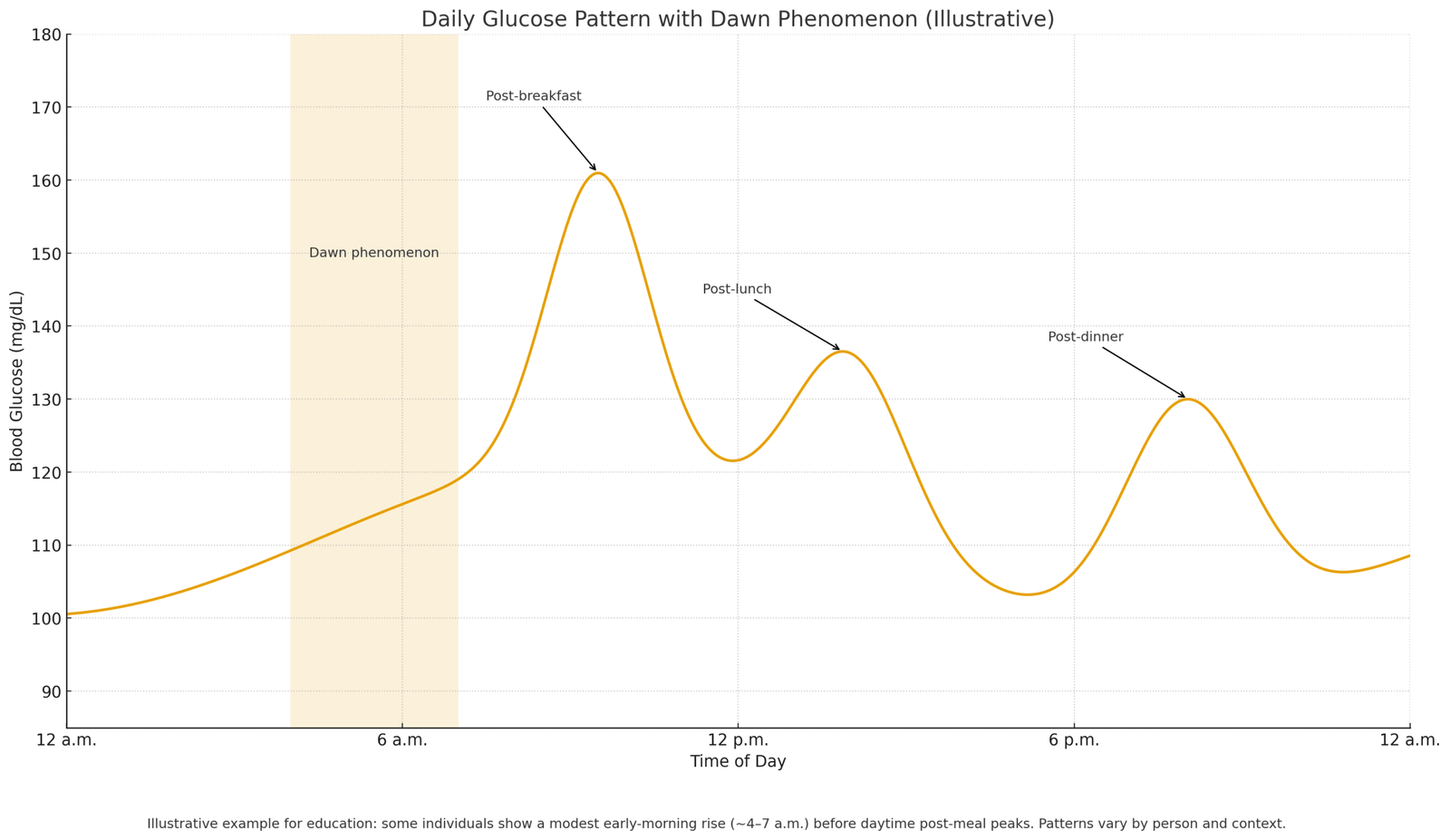

Yes. The dawn phenomenon—a normal early-morning rise in counter-regulatory hormones (e.g., cortisol)—can nudge fasting glucose and insulin upward; sleep debt, shift work, and irregular bedtimes can magnify this effect and increase morning-to-morning variability.

They can. Acute stress, intercurrent infections, and glucocorticoids (steroids) increase insulin demand and hepatic glucose output, so fasting insulin may rise transiently; clinicians often recheck once the trigger resolves to separate short-term changes from a persistent pattern.

Positive islet autoantibodies suggest beta-cell autoimmunity; early or mixed phases can still show elevated fasting insulin as the body compensates, but trajectories may differ over time. Antibody status helps guide referrals (endocrinology/rheumatology), monitoring cadence, and counseling.

LADA (latent autoimmune diabetes in adults) is an autoimmune form that often progresses more gradually; early in its course, some individuals can show normal or elevated fasting insulin with signs of insulin resistance before secretion declines, which is why antibody testing and C-peptide context are useful.

CGM can reveal glycemic variability, dawn phenomenon patterns, and post-meal excursions that standard labs may miss; these data help clinicians personalize nutrition, activity, and medication timing even when HbA1c looks acceptable.

Intervals are individualized, but many care plans reassess every 3–6 months alongside fasting glucose, HbA1c, and—when indicated—C-peptide or selective autoantibodies; some patients also use glucose logs or CGM time-in-range to translate day-to-day patterns into practical adjustments.

References

- American Diabetes Association. (Year). Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes. Retrieved from [https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2797383/].

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). Autoimmune Diseases Overview. Retrieved from [https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/conditions/autoimmune].

- National Institutes of Health.. Hyperinsulinemia and Metabolic Regulation. Retrieved from [https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6735759/].

- World Health Organization (WHO). Diabetes Fact Sheet. Retrieved from [https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes].

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Eating for Health & Managing Chronic Conditions. Retrieved from [https://odphp.health.gov/our-work/nutrition-physical-activity/food-medicine].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Managing Diabetes with Lifestyle Changes. [https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/living-with/index.html].

About the Author & Medical Review

Author: Dr. Muracle John— Health writer focusing on endocrinology and metabolic education for a U.S. and global readership.

Medical Review: Dr. Kelly Wood — Endocrinology. Reviewed for accuracy, scope, and educational balance.

Editorial Note: Educational content only; personalized decisions should be made with your licensed clinician.